A colleague and I once pioneered using levels of edits to help manage the workload through our content department at a large high-tech firm. We rolled out the concept and refined it over time, all in the name of efficiency and time to market. What we were really trying to do was save our sanity.

We failed.

Or rather, the whole endeavor of developing and releasing educational content through a single in-house unit failed. All the work—from course design to release—was eventually outsourced. But I learned something valuable from the experience. (And I hope others did, too.)

You can’t outsource quality.

I think that’s as true in today’s world of generative AI as it was “back in the day” when I was a technical editor. But how does editorial refinement work in today’s hungry market for “easy” content? Let’s look at how it used to work, how people would like it to work, and how it might work better.

The Long Tail of Levels of Edits

The idea that content refinement can require more than one level of edit—or an editorial funnel—has been around in some form since the mid-1970s, thanks to university contracts with the U.S. government. (Yes, I said that!) Folks at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Cal. Tech. first defined nine types of edits across five levels in their seminal work “The Levels of Edits” in March 1976.

The authors intended to impose a “sense of organization and rationality” on the editorial review of technical manuscripts. The goal was for each publication to “receive the highest level of edit consistent with the time and money constraints put upon it.”

From deepest to most superficial, the five levels of edits were:

- Substantive

- Mechanical and Language

- Copy Clarification and Format

- Screening and Integrity

- Coordination and Policy

Not to be outdone, the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) refined these five down to four and then three in 1994:

- Full Edit

- Grammar Edit

- Proofreading Edit

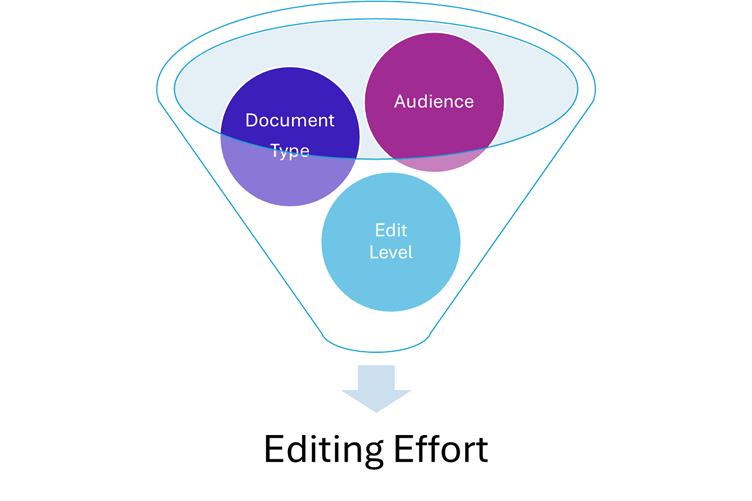

More importantly, LANL matrixed the edit levels with the types of documents (SOPs, white papers, brochures, etc.) and audiences (the public, laboratory partners, scientific peers, etc.). This was the first time I had seen the balance of needs shift from an internal focus (the organization’s needs) to an external focus (audience acceptance).

Importance of Quality in the Equation

Then came the contrarians.

In the spring of 1995, David E. Nadzeijka argued in “Needed: A Revision of the Lowest Level of Editing” (Technical Communication quarterly journal) that the last or most superficial level of editing, the proofreading or coordination level, needed some rethinking. He posited that most audiences would accept a typo or two but not logical or factual inconsistencies and certainly not plagiarism or copyright infringement.

And there it was—the final turn of the screw. The audience’s need for quality content would seem to outweigh any purist’s interest in conformity to stylistic convention.

In her seminal 1994 book, Managing Your Documentation Projects, JoAnn T. Hackos instructs us to “define the level of quality to be achieved” by a document and plan resource requirements accordingly. While she acknowledges LANL’s consideration of the audience’s perception of quality, she takes the concept further. She encouraged communicators to use “external measurements of quality,” including customer satisfaction surveys, results of usability testing, and increases or decreases in customer-service requests.

These external measures can lead us to define a “minimal level of quality acceptable by the organization.” However, she doesn’t discount the organization’s internal comfort level with content attributes such as organization, style, and accuracy. Instead, she reminds us that these attributes should be part of good processes, including good project management and well-trained staff.

This push-pull between internal and external definitions of quality content spilled over into our efforts, however imperfect, to define levels of edits for the organization I mentioned earlier. My colleague and I tried to define publication-readiness for various instructional materials that came across our desks.

(Aside: I confess it was tough for me, a former university writing instructor, to abandon the idea of a grading rubric that defined quality levels. However, a rubric often relies on levels of writing mastery as determined by a particular profession, not an organization’s or audience’s needs. A rubric is probably better applied during the hiring process when you are evaluating writing and/or editing samples from a prospective employee or contractor.)

Ultimately, we came up with a list of 11 quality points that we could then package into editing practices (levels), matrixed to types of instructional materials, and suggest a flow through the course development process. Our goal was to assist the department’s project managers in planning the releases of courses and materials.

Here, then, are our 11 points of content quality from most time-intensive for an editor to least:

- Purpose and scope meet the audience’s needs

- Contains only details appropriate to the target audience

- Is logically organized and developed

- Uses quality graphics appropriately

- Demonstrates precision/accuracy (consistency), clarity, and smooth flow

- Is localization-ready*

- Follows the organization’s style guidelines

- Adheres to requirements from the organization’s legal department

- Contains no obvious grammatical errors

- Contains no spellos, typos, or other gross mechanical errors

- Contains no publication-readiness errors (e.g., pagination errors, broken links, etc.)

(*Note: No offense to my localization friends, but not all our courses were localized. So, this requirement moved up and down the ladder or combined with #7, depending on its applicability.)

We packaged the first three quality points under the label “developmental edit.” I usually took those on, carefully examining a detailed table of contents and sample sections. In our thinking, a developmental edit was required early in the content-creation process for instructor-led courses about particularly complex subjects, such as a computer operating system.

Alternatively, for a course brochure, we’d suggest a check only for quality points 8 through 11. These comprised the minimum level of editing that our marketing partners expected. Eventually, we developed checklists to help with uniformity across the editorial staff. It wasn’t a perfect system. But it worked for a time.

To summarize, by the end of the 1990s, the concept of measurable—especially, externally measurable—content quality began to merge with the original concept of levels of edits. One could argue that the concept of measurability actually started to replace levels of edits. Additionally, the concept of quality processes came into play, thanks to the growing popularity of the continuous improvement movement and Six Sigma.

With all these factors in the mix, we could only hope to end up with quality content well-suited for our intended audiences. What the editing effort looks like in the mix, however, grows a bit fuzzy.

The “X” Factor and AI Editors

Into this editorial complexity, one day in the late 1990s, stepped an annoying little digital beast nicknamed “Clippy.” The animated paperclip offered unasked-for assistance in all Microsoft Office products, from save-your-file reminders to spelling corrections. While Clippy was relatively short-lived (and mourned by almost no one), the concept of on-screen writing assistance was not.

Thus, spell-checkers and grammar-checkers grew up in and around our favorite authoring software. Some were native, some were plug-ins, and some were customizable (with internal style guidelines and terminology, for instance). All exist today.

Moreover, they exist alongside two other digital behemoths: online content analytics applications and generative AI.

Content analytics, even with all their shortcomings, give us one avenue to measure how our audience perceives the quality of our content. From engagement and impressions, we might be able to deduce our content’s usefulness, maybe. However, these metrics are not a total replacement for the quality measurements that Hackos advocated for (surveys, customer service data, and usability testing). Those measurements tell us—sometimes in excruciating detail—what our audience actually thinks of our content and gives us direction for improvement. Some combination of metrics and measurements is needed. (For my take on content metrics, please review my blog post “5 Intersects of Content Strategy and Project Management (Part 5)”)

Similarly (or maybe not), generative AI, even when it is applied to editing and regenerative work, is not a replacement for the holistic determination of the quality of a piece of content: meeting the audience’s needs in the best time (when), in the best place (where), and in the best format (how). Even when we feed AI all the content parameters and quality guidelines we can compose, the outcome can never be more than what one program in that one instant in time could derive from the (older) content it was trained on.

(For some ideas on how to use generative AI for the regeneration of existing content, please review my blog post “AI Prompting for Bloggers: My Trial-and-Error Discoveries.”)

The tendency for generative AI to hallucinate (make up terms, facts, and sources) is well-documented. The fact that AI can infinitely perpetuate those errors is horrifying. My colleague Scott Abel recently wrote a Substack post describing how a mistranslation spawned the nonsense phrase “vegetative electron microscopy,” which AI then perpetuated.

Perhaps less well-documented is AI’s tendency to be inconsistent with itself. Geneticists in the Mass General Brigham healthcare system recently noted variability in AI results even when the AI was presented with the same problem and data set. The variability has two flavors: Drift (changes in model performance over time) and Nondeterminism (inconsistency between consecutive runs). Not very reassuring!

Still, we can ask Grammarly or Poe (or any other generative AI program) to check the grammar, spelling, punctuation, and consistency of voice and tone in a piece of text. We can even ask it to apply a standardized set of style guidelines, like AP Style. And we’ll get something useful in return, though, in my experience, the result will still contain a few errors. For example, in this blog post, Grammarly insisted that I replace the phrase “levels of edits” with “levels of editing.”

What is missing in generative AI right now is the X factor that a well-trained, well-informed human brings to content creation and review. It is a deeper contextual analysis plus the experiential judgment that says, “I heard my audience say X, Y, and Z, I know that A, B, and C are key contextual/organizational considerations, and I understand that Q, R, and T are in the works in the future, so here is what is needed in this piece of content.” The X factor is, in short, the kind of judgment I used when conducting a developmental edit (and creating a content strategy for that matter). And it is the kind of judgment, quite frankly, that often goes into developing an AI prompt in the first place!

Toward New Levels of Edits

So, where does all this leave the important idea that third-party editing contributes to the quality of a piece of content?

Well, that’s a matter of trust in today’s world.

If I go back to the 11 points of quality that my colleague and I outlined for our department, I can say with some confidence that an AI editor can tackle items 9 and 10 with reasonably effective results:

- Purpose and scope meet the audience’s needs

- Contains only details appropriate to the target audience

- Is logically organized and developed

- Uses quality graphics appropriately

- Demonstrates precision/accuracy (consistency), clarity, and smooth flow

- Is localization-ready

- Follows the organization’s style guidelines

- Adheres to requirements from the organization’s legal department

- Contains no obvious grammatical errors

- Contains no spellos, typos, or other gross mechanical errors

- Contains no publication-readiness errors (e.g., pagination errors, broken links, etc.)

The caveat is, of course, that you should not be feeding proprietary content into a public AI tool.

If you had a closed system and a customized tool, you could turn an AI tool loose to also review content for items 7, 8, and 11. You’d really have to cross your fingers and hope that AI, in tackling this level of review, didn’t change the intended meaning of any sentence, paragraph, or section.

Ironically, this “meaning shift” concern introduces a new level of edit in the modern world: Review the changes made by AI to uncover any significant shifts in meaning. But, of course, that kind of review entails the reviewer knowing the intended meaning of the content (for its intended audience and purpose) to begin with. So, we are back to asking reviewers to use their X factor to help ensure the quality of the content.

Can we stop our quality control efforts at that point? Maybe. When I gave a workshop to technical communicators about types of content review a couple of years ago, I listed for them some situations in which they could consider curtailing or combining content reviews:

- The content is temporary and has little impact

- The content is not technical, complex, or high-impact

- The content has to be preserved verbatim

- The content is meant to show personality, not expertise

- The schedule demands it (but don’t undermine your opportunity to negotiate!)

I also urged them never to skip a quality step or review when working with “life-saving” content. Nor, I would add, in a nod to Nadziejka, should you skip them in “reputation-saving” situations either.

Finally, none of this argument negates the immeasurable contributions to content quality of good process and good people. I love to quote my friend Erin Schroder on this point:

- You don’t need AI—You need a content strategy

- You don’t need AI—You need a sensible and efficient site structure

- You don’t need AI—You need user research

- You don’t need AI—You need focused content design

- You need a foundation and drywall before you add the smart thermostat!

Admittedly, we have yet to discover the true limitations of generative AI in the refinement of text. AI is evolving perhaps faster than our capacity to understand it. For now, can it help us recast existing content for a new audience? Yes, if we give it enough information. Can it help us determine if our content is fresh, unique, and well-positioned in the universe? Likely not—yet. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t find ways—or ask our tool-developers to find ways—to engage it in helping us move toward the true definition of quality content: content that meets the audience’s needs when, where, and how they need it.

Read more about safeguarding content quality against AI “slop” in my May 2025 blog post.

Discover more from DK Consulting of Colorado

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

5 thoughts on “Leveling an Editorial Eye on AI”