Designing online content sensitive to user differences has been our responsibility for at least 20 years – in the U.S., since the advent of Section 508 requirements. During that time, our awareness of inclusivity has evolved to include (pun intended) neurodiversity, a term coined in the 1990s by Judy Singer.

Nick Walker, Ph.D., defines “neurodivergent” folks as having “a mind that functions in ways which diverge significantly from the dominant societal standards of ‘normal.’” (See her helpful blog post “Neurodiversity: Some Basic Terms & Definitions.”)

The mind functions differently. That definition encompasses folks with dyslexia, autism, dyscalculia, ADHD, anxiety, and a neurological injury. It also includes me, a person with migraine disorder. Or it should.

Migraine is typically not listed among the conditions commonly associated with neurodivergence. However, the medical community defines migraine as a neurological disorder. More on that later.

Included in neurodivergence or not, my experience as a neurologically challenged person has influenced my career – as a content creator, leader, and team member. I share my insights here – along with some tips on how you can design accessible content for someone like me.

Accessibility Awareness Evolves

When I worked as a technical editor at a high-tech corporation, I was voluntold to contribute to a U.S.-wide effort by company technical communicators to define internal standards for something called Section 508. I had never heard of it.

According to regulations.gov:

“Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act (29 U.S.C. 794d), as amended in 1998, is a federal law that requires agencies to provide individuals with disabilities equal access to electronic information and data comparable to those who do not have disabilities, unless an undue burden would be imposed on the agency.”

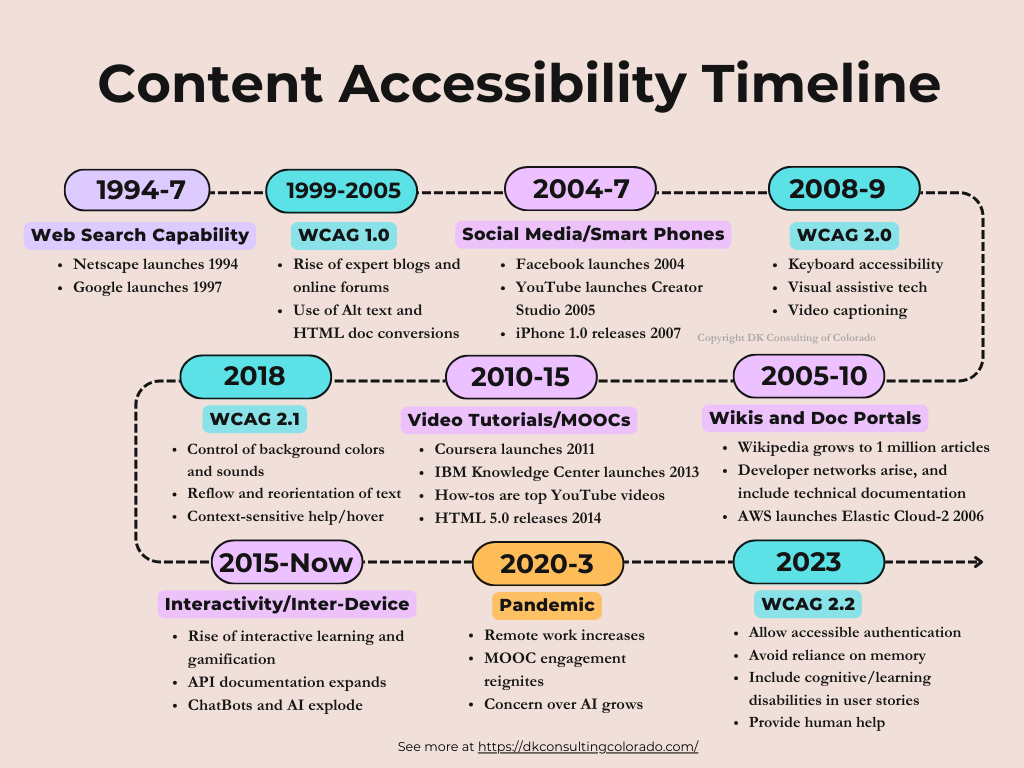

Technology companies selling software and hardware to the government had to meet these requirements starting June 1, 2001. At about the same time, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), published by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) in 1999, gained more prominence. This was the beginning.

Content Accessibility 1.x

For technical communicators in the very early 2000s, accessibility compliance mostly meant creating online help that was friendly to screen readers. (At that point, we didn’t design much technical content for the web; but remember, Google, which debuted in 1997, was new back then.) So, we dutifully added alternative text to graphics and ensured that tables and lists had descriptive introductions. Technologists worked on HTML coding and conversion requirements for content that had to be packaged outside of the then-propriety PDF.

(Side note: The Section 508 work I participated in wound up as a chapter in the third edition of Read Me First!: A Style Guide for the Computer Industry [December 2009].)

When web content exploded a few years later with the advent of wikis and documentation portals, complying with accessibility requirements became more complex. (For context, social media arrived in 2004 and smartphones in 2007.) Guidelines for accessibility included not only alternatives for text and graphics but also:

- Keyboard accessibility support.

- Navigation assistance.

- Zooming capability and other visual enhancement features.

- Pop-up interactivity, including the capability to turn off pop-ups.

- Alternative routes to assistance (including, yes, call centers).

With the advent of YouTube, online instructional videos, and later Zoom calls, came the need for video captioning. When interactive microphones became more technically sound, voice control capability answered the call. Threaded through all these miracles was the demand for translatability and the need for controlled, simplified language.

Content Accessibility for the Neurodivergent

Awareness of neurodivergence and its impact on content design is relatively recent. The W3C formed a working group in the spring of 2021, but the topic didn’t start appearing in my search crawlers until late 2022. The WCAG 2.2 guidelines were released in October 2023.

The pandemic might well have played a role in broadening accessibility awareness, with many having to work and learn remotely through sometimes hastily developed user interfaces. But certainly, advocacy for the neurodivergent over the past few years has given us additional audience needs to consider.

“Inclusive design requires supporting variations in cognition,” said Amy Grace Wells during a February 2023 presentation on design for cognitive accessibility. She points out that designing for cognitive differences is more than an “edge case” because 20% of your content’s consumers might be neurodivergent.

An important tenet of designing for neurodiversity is to lower the user’s cognitive load and memory requirements by reducing complexity. The overarching goal is to enable the user to complete a task without distractions or confusion, what Wells calls “lowering the hurdle.” She reminds us that even adding boldface or other special formatting to content can increase the user’s cognitive load.

The W3C paper “Making Content Usable for People with Cognitive and Learning Disabilities,” which supplements the WCAG 2.2 guidelines, outlines design guidelines for eight objectives. The authors ask us to help users:

- Understand what things are and how to use them.

- Find what they need.

- Comprehend and perceive through clear and understandable content.

- Avoid mistakes and know how to correct them.

- Focus by avoiding distractions.

- Progress through processes in ways that do not rely on memory.

- Receive help and support.

- Engage through adaptation and personalization.

The design guidelines emphasize using hierarchy and pattern to assist distinction and repeated designs for control and other important functions to assist memory. (They also extend their definition of discernable patterns to language and content organization.)

Plotting a course through these objectives might not be straightforward. To understand the expanded universe of accessible design, review the mind map poster recently created by Alice McGregor, an accessibility advocate. Her poster, in a nod to WCAG 1.0 topics, includes four questions for content designers to consider. Is your design:

- Robust (accessible through multiple devices)?

- Understandable (offering up easily comprehended content and functionality)?

- Perceivable (consumable even if one of my senses is impaired)?

- Operable (navigable even when I am using assistive technology)?

What Migraine Is and Is Not

In this newly expanded arena, my sense of self as a content designer collided with my sense of self as a long-time migraine patient. These guidelines not only aligned with my professional goals, but they also squarely hit my personal needs bullseye.

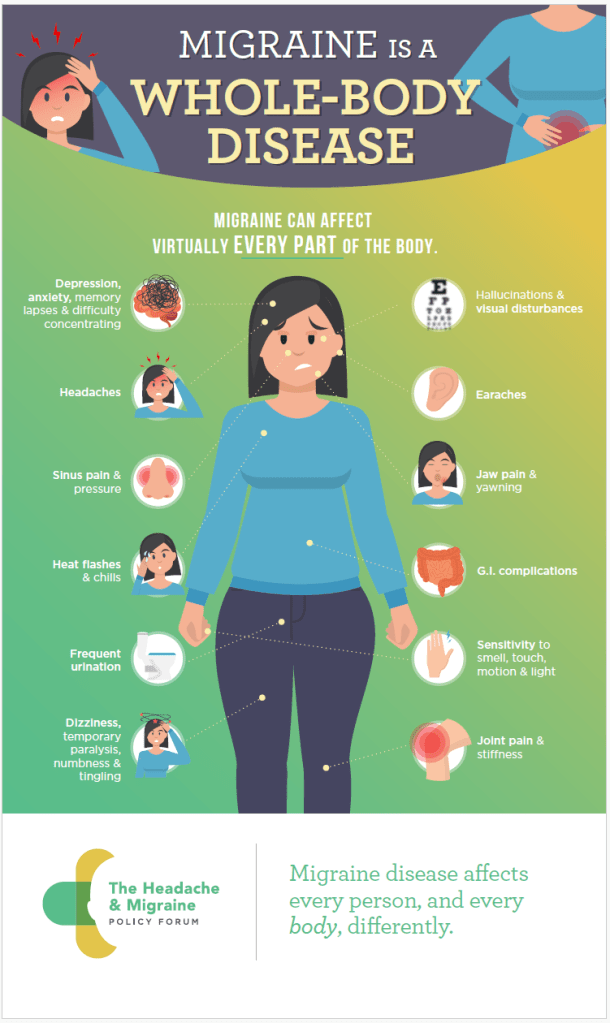

Let me be clear about why. Migraine is not just a headache. Migraine. Is. A. Neurological. Disorder.

Soooo yes, the headache is awful. However, a migraine attack can involve symptoms throughout the body. Some, like vomiting, are icky. Others, like visual aura, which I experience, are difficult to explain. (Imagine a jagged lightning bolt across your field of vision.) We also can frighten our family members with temporary aphasia, chills/hot flashes, and short-term loss of feeling or control of our extremities.

We can recover from an attack (often within a few hours by using a “rescue med.”). But we cannot be ignored.

Worldwide, 1 billion people live with migraine; 39 million in the U.S. That’s 1 in 5 women, 1 in 16 men, and 1 in 11 children. In fact, migraine is the third most common and second most disabling disease in the U.S. (These statistics and additional information are available from the American Migraine Foundation.)

Folks with migraine disorder often have auditory, visual, cognitive, and/or physical sensitivities, which manifest more strongly during a migraine attack. Most of us have triggers in one or more of these areas. Some triggers we can control, such as:

- Flashing lights

- Strong smells

- Loud noises

- Dehydration

- Intense exercise

- Stress

- Lack of sleep

Others we cannot, such as:

- Hormone levels

- Poorly healed injuries

- Brain chemistry

- Other inherited factors (yes, it’s in our genes)

That’s why migraine disorder is so complex and why it’s different in different people.

These sensitivities impact our lives and choices in ways neurotypical folks might not understand. For example, I turn down invitations to indoor arena events, such as basketball games and concerts, to avoid triggering my sensitivity to flashing lights and loud noises. (Event planners, please take note!) In fact, I must monitor and moderate more than you’d think, which is sometimes exhausting. More on that in another blog post.

These sensitivities also impact how we interact with online content, including televised content. I turn away from web ads and TV commercials that race rapidly through a sequence of images or rapidly flash a brightly colored line of text. I don’t care how cool it is; I cannot look at it.

Tactics for Accessibility in Content Design

Successfully designing online content for someone like me involves more than removing flashing elements, though that’s a start.

I support the recommendations others have made for designing content for the neurodivergent:

- “Cognitive Load Theory” on the MindTools website describes how the brain processes information (including the Sweller theory) and provides some practical advice.

- “How to Write Dyslexic Friendly Web Content: Colours and Fonts” on the Scope website covers some basics for accessible content design.

- “Simple Writing Is Better Writing” by Ettie Bailey-King reminds us to consider both physical and cognitive diversities.

- “Designing for People with Dyscalculia and Low Numeracy” by Jane McFayden, Rachel Malic, and Laura Parker offers a DOs and DON’Ts list for presenting numbers and digits.

- “Designing With the Autistic Community” by Irina Rusakova offers examples of improved page layouts for websites.

- “Neurodiversity and Designing for Difference” by Nia Campbell advocates for respecting users’ differences and provides tips for writing and formatting online content. (Note: Campbell also references some of the articles on this list.)

- “Mind Your Marketing: Why Brands Shouldn’t Ignore Neurodivergent Consumers” by Melissa Harvey describes how social media accommodates neurodiversity.

Below are my recommendations.

First, here are some DON’Ts:

- Do not allow auto-start for videos included in the content or post.

- Avoid loud noise and discordance in videos.

- Avoid red font.

- Avoid “dancing” text and gifs.

- Do not interrupt the text flow with multiple quote-outs and special offers.

- Avoid brightly colored backgrounds on pages and pop-ups.

- Avoid multiple pop-ups on a single landing page.

- Avoid obtuse language, idioms, similes, and metaphors.

And here are some DOs:

- Include signposts in the text, such as hierarchical headings.

- Keep the text in headings succinct and distinct.

- Design the text for scannability.*

- Allow the user’s mind and eyes to rest with simple layouts and lots of white space.

- Allow the user to control the volume of audio and video content.

- Allow the user to close or turn off a video segment in the content or post.

- Offer a transcript of video or audio content.

- Offer an audio recording of crucial content, if possible.

*See my previous blog post “Creating Online Content for Your Customers: Scannability.”

Many tenets of sound, minimalist content design align with these recommendations. Thus, these recommendations should ring true for an experienced content designer. Nevertheless, on behalf of all neurodivergent users everywhere, I repeat this plea: It’s time for us all to be more accommodating.

Writer’s Note

In 2023, I completed a training course on migraine advocacy through the American Migraine Foundation. I freely admit that I would like to see migraine disorder included in the definition of neurodivergence. That said, I know from my training that people with migraine disorder often have comorbidities, such as anxiety, that overlap the current definition of neurodivergence.

If you would like to know more about migraine disorder, please visit and support one or more of these U.S. organizations:

- American Headache Society

- American Migraine Foundation

- Association of Migraine Disorders

- CHAMP (Coalition for Headache and Migraine Patients)

- Migraine Again

- Migraine at Work

- Migraine World Summit

- Miles for Migraine

The featured image at the top of the page is by Vinicius “amnx” Amano and is available through Unsplash.

Discover more from DK Consulting of Colorado

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Neurodivergence and Content Design: The Migraine Edition”