User personas, my corona! Who needs a collective when a real representative will do? No, I am not dissing the research and analysis that ultimately yields a relatable on-paper user. Nor am I endorsing a beer brand.

What I want to share is what worked for me when I had to characterize some brand new audiences to my in-house team of technical information developers.

My task was to help our information developers understand the folks who would be installing, managing, and maintaining a complex data storage product in a data center environment. A simple, generic profile of a generic data center technician wouldn’t do. In fact, the corporate data centers had layers of data center personnel, all of whom had specific tasks they performed on our product.

So I set out to make sure that the team could access “real” folks who represented those layers of interaction. Here are the steps I took:

- Research the tasks and backgrounds of typical data center employees

- Gather interview questions and contact information for interview candidates

- Conduct and record face-to-face interviews with target audience members

- Develop 3-page “real” user profiles for my information development team

- Provide context to the team for those profiles

Conduct Background Research

To be honest, I did take some steps toward creating more generic user personas when I first started my audience research. I did the typical things. For example, I looked at Onet Online to view the typical tasks for network and computer systems administrators. I also uncovered some generic personas for related technical products at the Fedora Project (example below).

Because my target audiences were working in relatively new positions within our corporate infrastructure, I also looked up job listings on our corporate website. I then compared those to job listings for similar roles that appeared on our competitors’ corporate websites.

From this research and from some initial discussions I had with our user-facing product management and software architects, I was able to form some general ideas about our new target audience. I even captured some of those in a draft user persona document. (Many thanks here to Joann Hackos for sharing some user persona templates with me.)

The challenge was that my “key audience segments” had discrete roles that could not be easily characterized by examining these general descriptions. And those roles were evolving as corporate evolved its cloud strategy. So while I had a provisional persona for my target audience, I needed more.

Set Up Interviews

To find “more,” I pressed my management to allow me to conduct user interviews. With help from my manager and my partner content strategist, we engaged our services and product management partners to help us find “real” technicians and field engineers for our interviews.

Sometimes this meant that we had to first “interview” their managers. In other words, we had to explain ourselves. The managers wanted to know what our objectives were, how long the interviews were going to take, and what kinds of information we were seeking. All of that is perfectly reasonable; no field engineering manager wants their carefully organized work assignments interrupted for long.

So we gave them the parameters of our interview sessions and tried to generate excitement for our final product – an internal website tailored to their teams’ needs. We cringed when they tried to speak for their employees, but appreciated their insights into the work environment and their expectations for task completion.

With these insights, we developed a list of interview questions that we intended to ask each interviewee. We then stepped through that list of questions with the full team of information developers. With their expert advice, we refined our list of questions to encompass these areas:

- Background, including experience with products similar to ours

- Job function

- Typical work week (including how their workload broke down, with percentages)

- Frustrations with their current interactions with product content

- Desired improvements in product content

- Preferences for formats and channels through which to receive product content

- Other types of content they consumed and their preferred channels and formats for that content

Conduct the Interviews

By working through internal channels, we were able to set up appointments at sites where our target audience would first encounter our product. We set up an entire day at each facility. The security was amazing but reassuring.

Accompanied by our lead product manager, we first sat down with our interviewees as a group for some general questions about the data center. This kick-off meeting set everyone at ease and reminded them of our intentions. Next, typically, we would enjoy a tour of the facility.

Then it was time to get down to work. Because of security concerns, we usually couldn’t be on the data center floor, so we couldn’t observe our target audience performing real work. But we were able to set up a conference room for conducting private interviews.

With our notepads in front of us and a recording app running on my mobile phone, we stepped through our list of questions. Some interviewees needed more prompting than others, and some didn’t want to be recorded. I always asked before pushing the record button or snapping a photo.

After the first interview, I learned to make a notation on my notepad of what point in the recording certain crucial points were made or when the topic changed. Whew! That saved me some time later on!

Create Real User Profiles

After we returned to work, I organized my notes, listening to the audio recordings while I filled in blanks and captured key quotations.

I realized early on that capturing the real words from real users would be the best way to bring the interview experience to our information developers. That way, they could experience the personalities of the interviewees firsthand – see where each interviewee placed emphasis.

The quotations were honest, insightful, and sometimes earth-shattering. One operations engineer told us that his team wrote their own documentation after initially learning the product “basics” from the product documentation; he called their use of our carefully prepared PDF manuals “one and done.” But he also admitted that “one of the biggest downfalls of our documentation is that is written by us, and we’re Ops Engineers – we’re not good at documentation.” Wow! How do you solve that riddle?

I organized each profile in the same way, using a template (admittedly in MS Word) that followed the flow I outlined for the questions (above). For readability, I included bullet points within the background, job function, work week, and job frustration sections. That way, I could fit all four sections plus a photo on the first page. Here is an example (with redactions):

I dedicated the next two pages of the profile to describing an interviewee’s interactions with existing documentation as well as their hopes for improvements in future documentation. For each major topic that an interviewee discussed, I wrote a subheading for context and chose a representative quotation.

The flow was organic, based on our question prompts and the interviewees’ own ideas of what we needed to understand. “It would be really nice to be warned that I shouldn’t guess at a certain step because I have to get it right, right now, or it’s going to come back to bite me,” one system administrator told us.

As I completed each profile, I sent each interviewee a copy and asked for corrections and additions. Most wrote me back that they were fine with what I had captured. Some sent me adjustments and additional information. One maintenance manager told me he was “honored” at what I had written because it made him look so impressive. (Yes, I teared up at that response.)

The resulting profiles also resonated with our information developers. They were impressed with the backgrounds of our new audience members, amazed at their workloads, and appreciative of their insights. The fact that I had produced several profiles from each trip had its plusses and minuses. The information developers could pick out common themes across the profile set, but it was a lot of content for them to wade through.

Put the Profiles in Context

To help bring context to the 10 or so user profiles I created, I tried several methods of synthesizing the information from our interviews and my research for our information developers:

- A slide deck that described the data center environment in which our audience worked

- A slide deck that summarized common characteristics and themes across all of the profiles

- A high-level flowchart of the escalation paths through the various operations and support groups

- A high-level flowchart of the lifecycle of a hardware product in the data center

- Graphic showing the relationships of each role to the product hardware

The slide decks and flowcharts gave them succinct overview information, which was especially important in an environment in which Confluence pages were proliferating. Plus these resources generated some useful questions that lead to some new discoveries. In particular, our information developers could see for themselves the differences between how our former users interacted with our product (and each other) and how our new target audiences interacted (or did not interact). Here is an example flowchart:

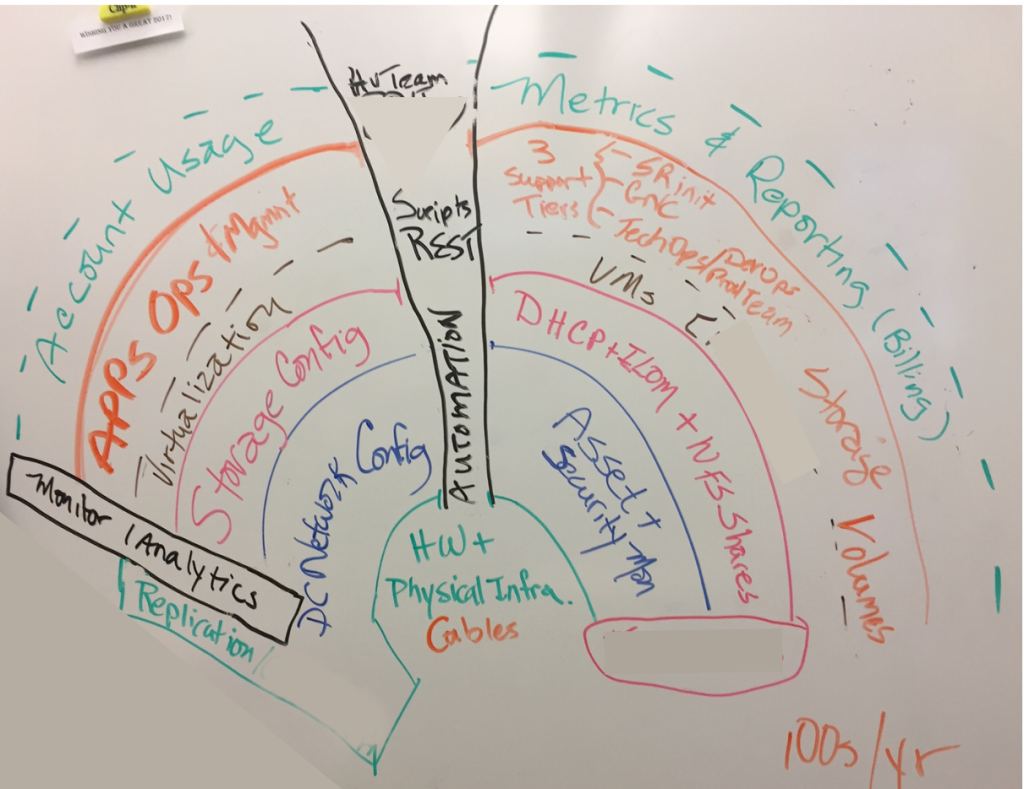

But what really resonated with them was my “rainbow” graphic showing how “closely” each role functioned in relationship to the actual hardware on the data center floor. I think they favored that rainbow partly because it was not a flowchart, and partly because I hand-drew it on the whiteboard in my cubicle. With various colored markers, we could draw arrows and bubbles while we discussed how certain information might impact certain roles. Here is one photo of that “rainbow”:

Gradually, our information developers began to grasp the whole new world that our product – and our product content – was stepping into. At times they were, admittedly, frustrated that the profiles and context documents did not answer some of the important questions about how certain tasks were to be performed. But since the new, data-center version of the product was still in development, they knew they were not the only ones struggling with those questions.

In some such situations, it helped that some of our interviewees made themselves available either in person or by phone to answer questions. It also helped that our content plan was flexible and that we had access to a “sandbox” version of our website in which to experiment.

You can read more about our flexible approach to a combined content audit and plan in my previous blog “How to Develop a Combined Content Audit and Plan.”

You can learn more about this team’s transformation journey by listening to the “Candid Conversations” presentation I recorded for the ConVEx 2020 conference.

You might also be interested in my blog “The Ownership Obstacle to Content Strategy and 5 Ways to Handle It.”

4 thoughts on “Tips for Developing a “Real” User Profile for a Content Strategy”